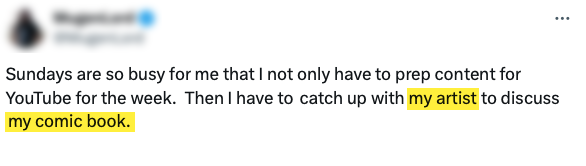

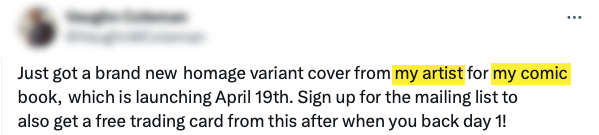

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a post about the most annoying meme of all time. Unfortunately, in some corners of comics social media, it ignited another writers versus artists debate, which was not my intention. Someone lamented that they wished my essay brought something new to the debate. Since I hadn’t intended it to be a part of the debate, that hadn’t even occurred to me—I just really hate that meme!

That said, I started thinking about how I collaborate on projects, how we can reframe the way that we define our collaborations. and how I’d like to be treated if I were approached with a work-for-hire gig that sounded good. Regardless, there are many creative approaches to make a collaboration equatable.

In the first part of this essay, I talked about giving your collaborators an ownership stake in the project.

Here are a few ideas…

My Privilege

I’m fortunate. I mostly work with friends, and my collaborations are the result of years of friendship with peers and colleagues. We share ownership, and most of my projects are back-end payment. Most of my collaborators aren’t neophytes, have had their share of ups and downs in comics, and have realistic expectations of how much (or little) money there is in independent comics. Many of them work in other fields, like storyboarding or illustration, to earn a living. Again, there are realistic expectations all around, we trust one another, and value the friendships over the collaborations.

An Arranged Marriage

I realize that not everyone is so lucky. For a lot of writers, they’re coming into this cold, with no connections to artists. And once you find an artist and agree to collaborate, how can you be sure it’s a good long-term fit? How can you, in good conscience, give away half of your dream project to someone you’ve just met, who you may or may not see eye-to-eye with in the long run? Can you and an artist you just met sustain a harmonious relationship over the course of years to tell this story—and possible sequels?

Of course, there’s no way of knowing if a collaboration will work, and it would be foolish for you to sign on to give away half of your project to a complete stranger.

Going from Contractor to Collaborator

You meet an artist, hit it off, and both are excited about the project. Maybe after a few pages, their enthusiasm wanes and they ghost you. Perhaps they’re halfway through your first issue and they get another gig—one that pays better—and leave you high and dry. Or maybe they finish the first issue and quit immediately afterward. Whew! It’s a good thing you didn’t offer them co-ownership, right?

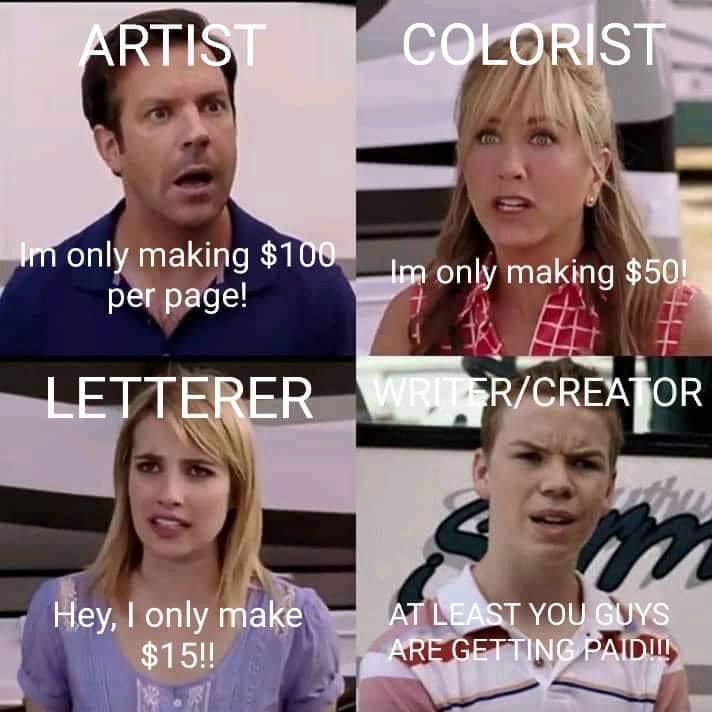

Now flip it. Look at it from the artist’s perspective. Your page rate has you strapped (comics are expensive!), but maybe they’re making about $6/hour on your book. As much as they may like you, and may like the book, their return on investment is comparable to a McJob.

If you really did hit it off with this artist, and really do think it could be the start of a long-term partnership, consider graduated vesting. Maybe after 4 issues of work-for-hire pay, your artist has earned 20% ownership of the book. You could even incentivize it something like this:

- issue 1: 4% ownership share

- issue 2: 8% ownership share

- issue 3: 12% ownership share

- issue 4: 20% ownership share

Make the vesting contingent upon completing 4 issues, so that if they bail after 2, you’re not out anything. But there’s an incentive to continue working together, and a promise that when the first arc is completed, there’s a bump in ownership. Issues 5–8 could work in a similar fashion, getting the collaborator up to 40%. Maybe issue 10 is the threshold where they become fully vested at 50% ownership.

These percentage examples are a little arbitrary, just to give you an idea how you can approach it. You can tailor it to your specific situation, of course, possibly with higher percentages per issue, or a longer/shorter time until reaching a full ownership share. The idea is to give your collaborator a sense of agency, rather than just feeling like a gig worker.

Be Flexible

Maybe your collaborator is cooking along and has to take an issue off due to family issues, deadlines at the day job, etc. If they’re not quitting but jut need a fill-in issue, maybe you pause the vesting and resume when they return, instead of them losing what they’d accrued because they missed an issue.

Advances Against Royalties

“How can I pay an artist a page rate and give them 50% ownership? It’s not fair to me.” You’re absolutely right. Even though art is a more time-consuming process, your working arrangement should be fair to all parties—you included. If you’re paying your collaborator(s) out of pocket, and they have a share of ownership, it’s entirely fair for their royalties to be paid after you’ve recouped what you’ve paid them, and after you’ve paid yourself the same amount that you’ve paid out. That’s fair.

So maybe it works like this: You pay the rate(s), Kickstart your book, and, from the profits, pay yourself. Only after you’ve been repaid and earned as much as your collaborator(s) have, will they see a share of the money earned from the campaign (or the direct market, or whatever).

Not Just for Artists

Yes, I used “artists” as the main example of collaborator here, but it’s applicable across the board. You can divide this down as much as you like: pencillers, inkers, colorists, letterers—all are valuable members of your team, and, at your discretion, can be given ownership shares. For books I’ve created or co-created, colorist Jason Millet has a share in Athena Voltaire, Ghoul Scouts, etc, editor Chris Murrin has a share in Ghoul Scouts, Evie and the Helsings, etc. It’s up to you. There aren’t any rules for how you can or should define your collaborations. Just make them work for you.

Get It in Writing

As always, and especially with friends, get it in writing, with help from a lawyer specializing in intellectual property.