Fighting the playlist mentality

A few weeks ago, I wrote an essay titled Proudly Autodidactic. I pretty much wrote it so I could write this one. I felt that I needed to explain where I was coming from before diving into this topic, which has been on my mind for a while.

In fairness, this may have an Old Man Yells at Cloud vibe to it for some of you. I hope not, but the risk is there.

So anyway, topic has been on my mind for a while, blah, blah, blah…

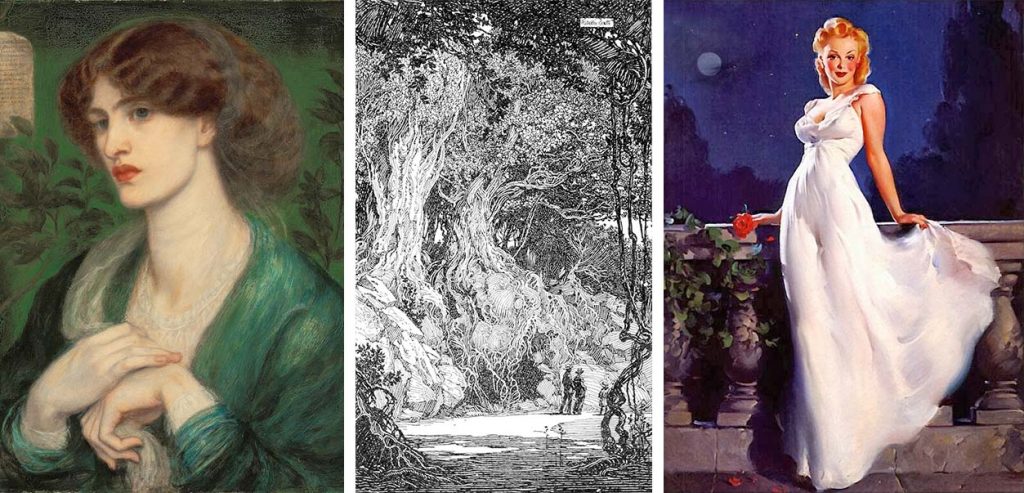

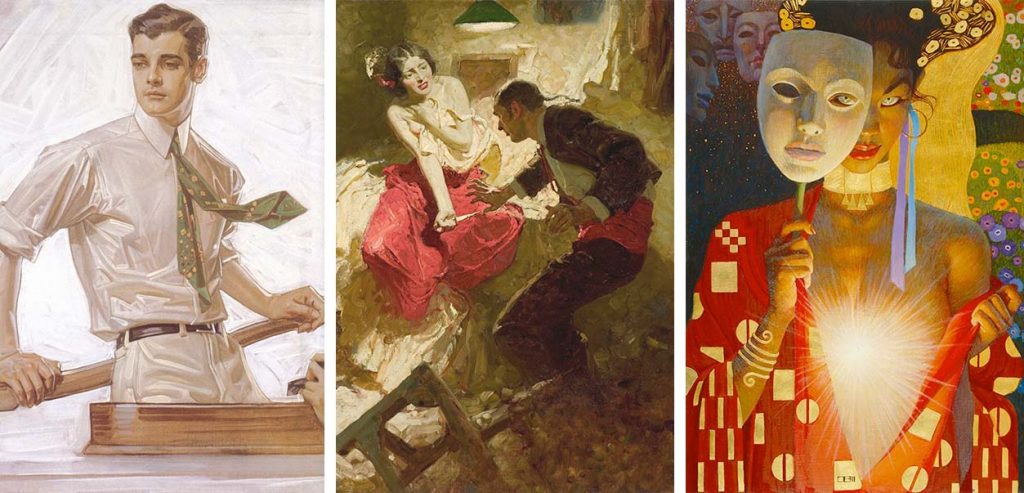

For the last four years, I’ve had the pleasure of teaching young artists in my capacity as a professor at Illinois State University’s Creative Technologies program. Because emulation has been a big part of my own artistic growth, I lean heavily into it in my classes, too. Of course, this is nothing new. Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Edgar Degas, and countless others learned the fundamentals of their craft by taking apart the work of the geniuses who came before them in order to understand how the work, well…works.

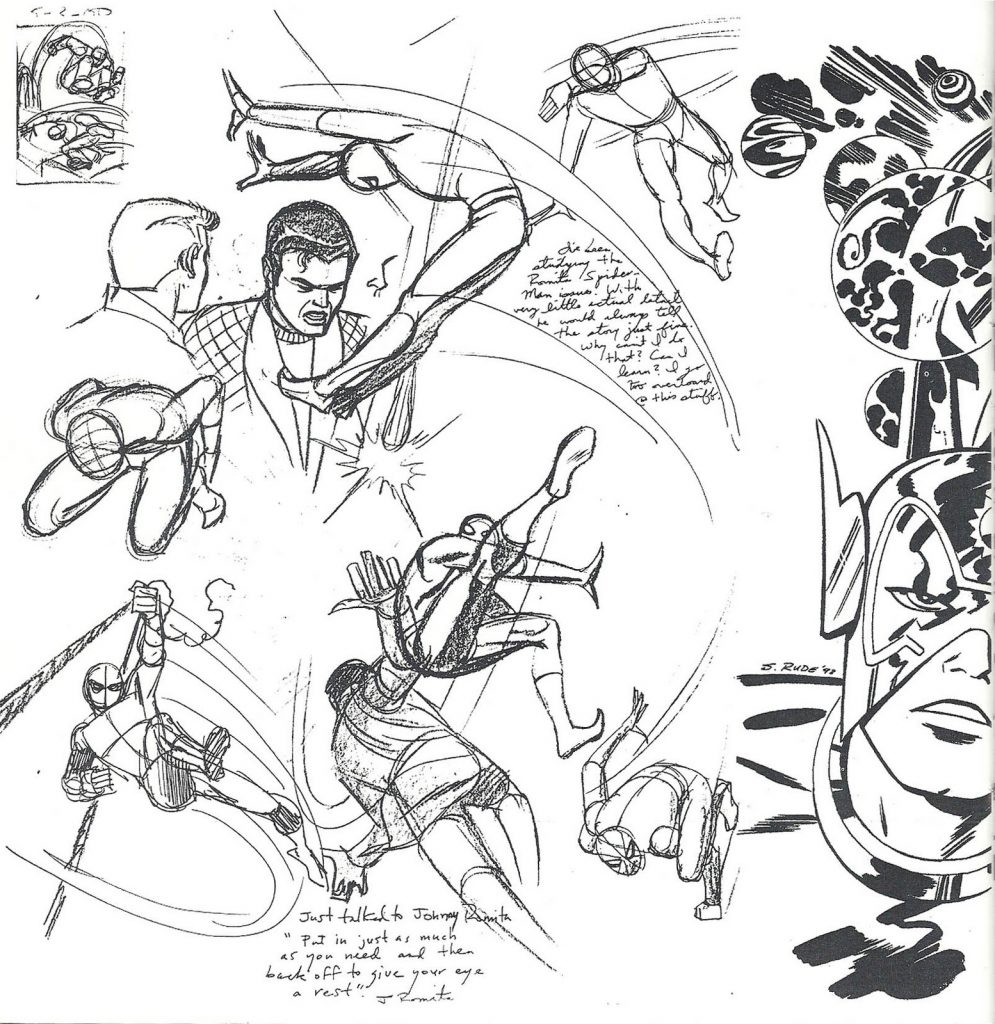

For me, it was learning about Steve Rude’s process, and how he studiously copied work into his sketchbook. Anything that impressed him as an artist, he wanted to figure out what made it tick. This kind of copying, of course, is different than what we all did as kids, where the objective was just to reproduce what we saw. The idea behind master studies is to understand what we see, and to apply that understanding to our own work.

The classes I teach are 75-minutes, not the longer 2-hour 50-minute studio sessions. With that in mind, and the other stuff we have to cover over the course of a 15-week semester, it’s not realistic to devote the necessary time to master studies. But we do talk about examining work that inspires us and reverse-engineering it in our own work through emulation.

Last spring, I noticed a phenomenon I’d never experienced in all my years of talking with artists. I sat with a student who showed me a jpg of work they admired, and I asked them about the artist. They didn’t know the artist’s name. The most information they had was that the artist was “someone I follow on Instagram. Let me see if I can find them.”

After 10 minutes of fruitless searching, scrolling through some of the 1,000+ artists they follow on Instagram, they shrugged and told me they couldn’t find the artist.

Seriously, it’s no exaggeration to say I was gobsmacked by this. There’s an artist who’s work you like enough to download one of their images and study, so as to incorporate some of that magic in your own work, but you don’t know their name? For someone like me—who has way too damn many art books as it is, and gets more and more every year, and jots down the name of every interesting artist they come across online or in conversation with other artists—this is unfathomable.

The convenience of a platform like Instagram, where artists’ work flashes across your timeline and the algorithm inserts new ones you may like (or artists and influencers who have paid to have their work inserted onto your timeline) is readily apparent. But the shift of young artists going from being active collectors of visual knowledge to passive consumers of a curated “playlist” is troubling to me.

I realize that just because it’s different from how I learned and assimilated influences, it’s not necessarily a bad thing. But after reading Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow’s Chokepoint Capitalism, and seeing how much of our culture is dictated by a few massive tech companies, it gives me pause.

Similarly, I had a different student who told me how much they loved comics, and how much they wanted to make comics. When I asked them about their favorite comics, instead of hearing comic titles and creators, I got a list of characters. And movies. And TV shows.

They did have some familiarity with the characters as they appeared in comics. Not by actually reading comics, but by watching YouTube recaps of the comics.

There’s nothing wrong with these recap sites, but if you want to make comics—whether you’re a writer, penciller, inker, colorist, letterer, or editor—there’s not substitute for actually reading comics. And studying them. Lots of them. Over and over.

I can’t imagine an aspiring film director limiting themself to watching movie/recaps and then feeling that they can direct a film. Or a writer that only reads Wikipedia recaps of novels. Or a musician that picks up an instrument and avoids listening to complete songs.

In both of these instances, these students are ceding their creative autonomy to revenue-generating algorithms. And that’s not great for the creative process.

So if you’re a young creative who’s reading this, I apologize if my thinking comes off as antiquated to you. But please consider rejecting the playlist mentality and embrace your nature as an artistic hunter-gatherer, seeking out cool work that inspires you.